Juliet Leonard, speech and language therapist, explains why boldly returning to early phonological awareness teaching impacts positively on children with delayed literacy skills.

Learning to read is an exciting step that generally receives a kickstart when a child starts at primary school. Watching a child go from recognising sounds, to blending them into words and on to early reading is a delight to see for teachers, parents, and carers. There is nothing quite like the moment when a child ‘becomes a reader’ – of anything and everything – from road signs to birthday cards, magazines and of course books.

Literacy is a vital strand in educational attainment; research shows that lacking vital literacy skills holds a person back at every stage of their life. Furthermore, this cycle impacts on future generations of families, having a long-term effect on social mobility.

Whilst a reading epiphany is sometimes seen in children as they move through Key Stage 1, the skills that they have been practising in their pre-school years and continue to practise in school are fundamental foundations for literacy development. Without these building blocks in place, literacy cannot continue to develop.

Emergent literacy skills, more commonly referred to as ‘phonological awareness’ are the ability to listen to and attach meaning to sounds, to hear rhythms and patterns, to retain these to blend them together and to be able to split a word into its sound parts.

Children who have not acquired and embedded these skills before they are introduced to phonemes and letters will struggle to develop their literacy skills. In addition, they may struggle to produce and blend sounds and words, making repeated sound errors. Their ability to start categorising words according to their sounds typically develops later and this impacts their learning, retrieval, and retention of vocabulary.

Stage over age

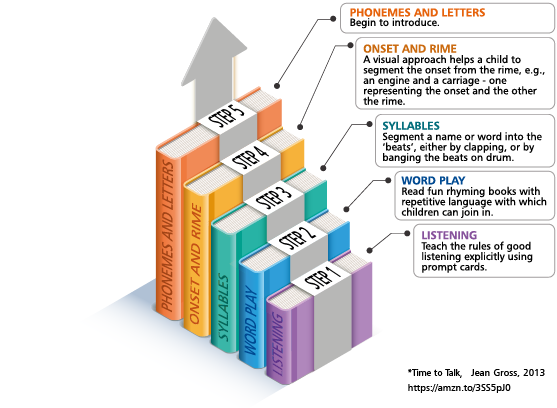

When children do not acquire literacy skills in Key Stage 1 as the curriculum might expect, it is important to revisit the phonological awareness ladder and consider which parts of this journey have not been attained by the child. It may be that skills were taught at a pre-school stage, but the child was not developmentally ready to take the concepts on board; or that these skills were missed due to environmental or situational reasons.

Children cannot gain a deep understanding of literacy without well embedded and well understood phonological awareness skills.

Listening is an area we take for granted; a skill which is used the most by students in schools and yet taught the least (Jean Gross, 2013)*. This is a vital early ingredient for successful learning.

A struggle to learn something can result in a disinclination or disinterest in that area. The ability to enjoy moments of play with words is fundamental for developing a love of literacy. In the recent The Link Live conference, Michael Rosen shared fond memories of playing with sounds and words, making silly sentences, and reciting favoured rhymes with his family.

The ability to segment words into parts is also crucial for reading, writing and vocabulary skills. Manipulating words into syllables, breaking the first sound away from a word (the ‘onset’) to leave the end (the ‘rime’) are ways in which children learn about sound combinations and begin to produce their own rhymes.

Only when all these steps are in place, is a child ready for the introduction of blending phonemes and reading words.

Phonological awareness is a vital pre-requisite for literacy development and difficulties can be an early sign of SLCN. Targeted support in the early years can make a long-lasting difference to both language and literacy development, as well as supporting early identification of literacy differences such as dyslexia, which require a more individualised approach.

*Time to Talk, Jean Gross, 2013 https://amzn.to/3SS5pJ0

Please login to view this content

Login