“My kids are slowly losing the ability to talk to other people.”

That’s what one parent said about the COVID lockdown period.

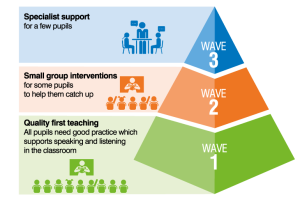

As a result, we are seeing more children who struggle with language – too many children to refer to speech and language therapists, and a greater need to target therapy at the ones who need it most. So, more than ever we will need a ‘Three-Wave’ approach.

Identifying needs

How do we know who needs help, and at what Wave? Nationally, there is ever-increasing interest in tools to identify speech, language and communication needs. I’ve been involved in Public Health England’s work on a tool called ELIM (Early Language Identification Measure) which health visitors are now using to spot two-year-olds with early signs of SLCN. Sadly, there isn’t the same national policy for older children, but if you are using Speech and Language Link’s tools you are well-placed to identify needs and target support accurately.

Myths and wrong turnings

When we look at Wave 1, I’m troubled by a trend in many schools to think we can close the word gap by simply introducing children to fairly randomly chosen new vocabulary – the ‘word of the day’ approach.

Teachers often focus on advanced ‘wow’ words, rather than the ordinary words that are useful right across the curriculum (Isobel Beck’s Tier 2 words, or the ‘Goldilocks’ words in the ‘Word Aware’ books and training). This is a really important distinction.

Suppose children come upon the word ‘incandescent’. It is a word they may enjoy, but are they going to need it regularly in their schooling? The word ‘constructed’, however, is going to come up in technology, in art, in literacy. So ‘incandescent’ should be briefly explained. But ‘constructed’ must be explicitly taught and practised until everybody can understand and use it.

We should never underestimate the gaps in children’s knowledge of apparently ‘easy’ words. A headteacher told me recently how he asked a Y5 class who knew the meaning of the word ‘fortnight’ (as distinct from the computer game). Only two hands went up.

So we need to choose our words carefully, teach them and then return to them regularly. I always suggest we draw on the science of memory and use spaced practice, using quick ‘word pot’ games to review taught words at progressively greater intervals: at the end of the lesson, at the end of the day, at the end of the week, at the end of the half term, at the end of term and so on.

Another common misunderstanding is that wide independent reading is the best way for children to broaden their vocabulary. Unfortunately, to work out the meaning of unfamiliar words from context a reader needs to be able to read and understand 95-98% of the other words in a passage. Many children with speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) will be nowhere near this figure.

Reading aloud to children, of course, can overcome this problem, so increasing the number of ‘read-alouds’ is important right now. One school scheduled daily whole-school story time; in Term 1 teachers positioned themselves around the school with a favourite book to read aloud to groups, in Term 2 older children read to younger ones, and in Term 3 children within the same class were paired, with stronger readers reading aloud to partners. In another school, staff made videos of themselves reading favourite stories aloud and posted them on Facebook so that children could listen to them at bedtime.

Top tips

1) Teach vocabulary children will use right across the curriculum

2) Keep going back to words taught earlier, or they won’t stick

3) Model new vocabulary yourself: “In the next fortnight – that means the next two weeks – our maths learning will be about…”

4) Reflect back what children say to you, adding extra vocabulary: “Oh, so your mum was going on at you, criticising you?”

5) Look at your timetable and see where there could be more opportunities for read aloud/paired reading sessions

Please login to view this content

Login