Glue ear is a term you may have often heard in relation to young children., or maybe it’s a term from your own personal experience with your children or from your own childhood. It isn’t always clear what it really means and I thought I’d take this opportunity to tell you a bit more about it.

First we should think about how the ear actually works.

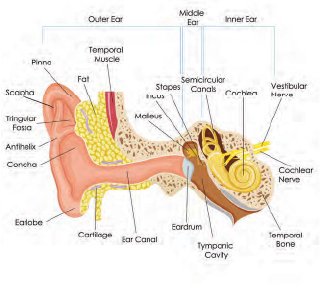

We have three parts to our ear: the outer ear, which contains the ear lobes and the ear canal; the middle ear, which has three tiny bones; and the inner ear, which is the organ of hearing and of balance.

Here is a detailed diagram to show you some of the technical terms:

At the end of the ear canal is the ear drum. This needs to be able to move with ease taking the sound that passes down the canal to the middle ear. The middle ear has three tiny bones that are linked passing the sound to the inner ear where the sounds are converted to pass along the auditory nerve to the brain.

The middle ear has a passageway from it to the back of the mouth so that the middle ear is filled with air. With young children, this tube (Eustachian tube) is very narrow and often a bit more horizontal. This means that when a child gets a cold, the fluid can go back into the middle ear and block it. It becomes thick and gluey and stops the tiny bones from moving.

Ok, so that’s the technical part!

The bit we really need to understand is how this affects a child; in particular, their listening and language development, and how can we help?

It’s an old trick, but put your forefingers into your ears firmly so there is no air passing down the ear canal. What does speech sound like and what does it feel like?

This is basically what is feels like (or close enough) when a child has glue ear. They can have a mild hearing loss of 20 dBL or a much greater one of up to 50 dBL. Their heads often feel full- just like yours did with your fingers in your ears.

So they can’t hear much of what is around them. On top of this difficulty, due to changes in the middle ear on a regular basis, their hearing loss might change daily!

Let’s think about how that affects a child learning a word. One day they hear the word “tomato” as “mado”, the next day as “demado” and the next as “oma o”. What the child is likely to do is to simply reject all three versions, not wanting to trust any of them. In other words they don’t pick up new vocabulary well.

The act of being deaf, albeit not fully, can be very tiring. The NDCS has very useful information about glue ear and its effect stating: “Changes in behaviour, becoming tired and frustrated, lack of concentration, preferring to play alone and not responding when called may indicate glue ear. These signs can often be mistaken for stubbornness, rudeness and being naughty. A prolonged period of time with reduced hearing can affect children’s speech development. For example, parts of words may not be pronounced clearly. Children with glue ear may also fall behind at school if they do not have extra support”.

It is important as teachers and teaching staff that we try to identify the children who may have glue ear. The funny thing is they are not always ill. They may have had a cold two weeks ago but they have persistent glue ear resulting in the hearing loss. We need to look out for behaviour changes and be alert to the signals they are giving.

Top Tips

If you know a child has glue ear then some basic communication tips can help:

- Always face the child when talking.

- Get down to their level.

- Don’t shout but use a strong and clear voice.

- Use visual support to help them focus and understand what you are saying.

- Use lots of repetition.

- Understand their potential level of tiredness.

Effects of hearing loss can be seen throughout their school life, as poor speech and language development can result in poor literacy and therefore poor academic levels- “vocabulary development at 5 years old is a powerful predictor of GCSE achievement”. Gross, J (2013), Time to Talk, Oxon, Routledge.

References

- NDCS: www.ndcs.org.uk/family_support/glue_ear

- Test your techn-ear-cal terms here: http://academic.udayton.edu/gregelvers/psy323/labels/ear.asp

- Gross, J (2013), Time to Talk, Oxon, Routledge.

Tell A Story By Phonic Books

The Tell A Story series are a new set of wordless books produced by Phonic Books, designed to be read with reception and nursery aged children and are ideal for children who need support in their language skills as a precursor to their reading skills.

They are simple, clearly drawn books using delightful animal characters, aimed at developing the child’s understanding and use of language, including developing specific vocabulary. The questions suggested for each page show a good range of levels of complexity fitting in well with the 5 levels of questioning described by Marion Blanks (where questions range from asking about the immediate environment and require concrete thinking, to questions that require a child to make basic predictions and to begin to use higher-order thinking skills; to those that require the child to use problem solving, predictions, solutions and explanations). Each book helps develop the child’s interest in stories, answering questions about the story and to explore a variety of emotions.

More details about the Tell A Story series, and Phonic Books can be found at www.phonicbooks.co.uk.

Please login to view this content

Login