Vocabulary teaching has been featured in a number of previous editions of The Link. It is appropriate to continue this focus given vocabulary’s crucial influence on attainment, behaviour, wellbeing and future employment1. While schools understand the impact of vocabulary instruction for improving reading comprehension2, they often do not realise that vocabulary also contributes to the learning of word-level reading skills such as phonemic awareness (orally breaking words into individual phonemes) and word reading.

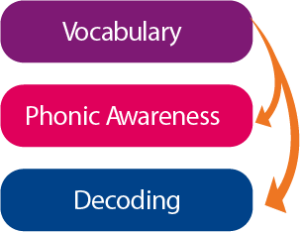

To better understand this relationship, we need to differentiate between two dimensions of vocabulary. Vocabulary size relates to the quantity of known words, whereas vocabulary depth reflects how well a word’s meaning is understood. Research suggests that vocabulary size is a predictor of children’s phonemic awareness and word recognition skills, as shown by the dotted arrows in the diagram. Studies indicate that vocabulary contributes between 4-15% of a child’s phonemic awareness skill3;4 and 6-11% of phonic reading5;6. The wide range of results is linked to the varying age groups and tests used in the studies.

One explanation of the relationship between vocabulary and word recognition can be found in the lexical restructuring hypothesis7 which suggests that words are initially stored as wholes, but as children learn more vocabulary the sound structure of words in the lexicon (internal dictionary) begins to overlap, for example if the word ‘cat’ is already known and the word ‘cap’ is introduced. In this way, vocabulary is stored in an increasingly distinct and segmented way that helps the child sound out words for reading.

Vocabulary continues to predict phonemic awareness and decoding ability until around the age of 8, which is when phonological skills typically reach maturity8;9. Thereafter, vocabulary mainly influences improvements in comprehension skills. Although vocabulary does not predict phonic reading after this point, it still has an influence on irregular exception word reading, such as the word ‘yacht’10;11. Exception words cannot be read purely through phonic decoding and require access to the child’s understanding of the word’s meaning. This aligns with the changing influence of vocabulary as a predictor of comprehension over decoding in Key Stage 2.

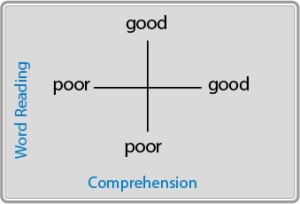

Literacy teaching in the UK is based on the Simple View of Reading12 comprised of two separate strands for word recognition and comprehension. The previous discussion has demonstrated that vocabulary and word reading are not separate but rather inter-related skills. My presentation at The Link Live 2021 conference described a vocabulary teaching approach that emphasises both sound and meaning aspects of words. Results showed that vocabulary instruction enabled young children to improve not only their vocabulary, but also their phonemic awareness and phonic reading.

Viewing vocabulary and word-level reading as highly connected skills13-15 presents a challenge for schools. Since vocabulary is linked not just to comprehension but also to word reading, teaching can be carried out in a more integrated way. For example, the sounds and the meaning of new vocabulary can be highlighted, as well as the link to print. Working on vocabulary in this way creates the opportunity to increase vocabulary as well as growth in phonemic awareness and phonics, particularly in younger pupils and potentially also for those who struggle with language and literacy.

Read on for more information…

If you are interested in developing your knowledge, understanding and skills in language and literacy development to support your work or future career, take a look at the ‘Language and Communication Impairment in Children’ (LACIC) course at Sheffield University. There are a range of postgraduate distance learning qualifications to choose from, including the Postgraduate Certificate (one year); Postgraduate Diploma (2 years) and MSc programmes (2 or 3 year options), all based on part-time online study supported by tutors and occasional study days.

The course would be relevant if you are you are a teacher, early years lead, SENCo, literacy co-ordinator, advisory teacher, educational psychologist, speech and language therapist or other professional with a specific interest in supporting children’s language and literacy development.

Please visit the website for further details: https://bit.ly/41Z7mYa

The university is offering 100+ scholarships worth £10,000 each for home fee paying students starting a taught course in 2023.

References

- Law, J., Rush, R., Schoon, I., & Parsons, S. (2009). Modeling developmental language difficulties from school entry into adulthood: Literacy, mental health, and employment outcomes. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 52(6), 1401-1416.

- Clarke, P. J., Snowling, M. J., Truelove, E., & Hulme, C. (2010). Ameliorating children’s reading-comprehension difficulties: A randomized controlled trial. Psychologcal Science, 21(8), 1106-1116.

- Dickinson, D. K., McCabe, A., Anastasopoulos, L., Peisner-feinberg, E. S., & Poe, M. D. (2003). The comprehensive language approach to early literacy: The interrelationships among vocabulary, phonological sensitivity, and print knowledge among preschool-aged children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(3), 465-481.

- Sénéchal, M., Ouellette, G., & Rodney, D. (2006). The misunderstood giant: On the predictive role of early vocabulary to future reading. Vol. 2. In D. Dickinson & S. Neuman (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (pp. 173-182). Guilford.

- Duff, F. J., Reen, G., Plunkett, K., & Nation, K. (2015). Do infant vocabulary skills predict school-age language and literacy outcomes? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(8), 848-856.

- Garlock, V. M., Walley, A. C., & Metsala, J. L. (2001). Age-of-acquisition, word frequency, and neighborhood density effects on spoken word recognition by children and adults. Journal of Memory and Language, 45(3), 468-492.

- Metsala, J. L., & Walley, A. C. (1998). Spoken vocabulary growth and the segmental restructuring of lexical representations: Precursors to phonemic awareness and early reading ability. In J. Metsala & L. Ehri (Eds.), Word recognition in beginning literacy (pp. 89-120). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Lee, J. (2011). Size matters: Early vocabulary as a predictor of language and literacy competence. Applied Psycholinguistics, 32(01), 69-92.

- Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., Rashotte, C. A., Hecht, S. A., Barker, T. A., Burgess, S. R., Donahue, J., & Garon, T. (1997). Changing relations between phonological processing abilities and word-level reading as children develop from beginning to skilled readers: A 5-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 33(3), 468-479.

- Ouellette, G., & Beers, A. (2010). A not-so-simple view of reading: how oral vocabulary and visual-word recognition complicate the story. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 23(2), 189-208.

- Ricketts, J., Nation, K., & Bishop, D. V. M. (2007). Vocabulary is important for some, but not all reading skills. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11(3), 235-257.

- Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6-10.

- Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B.(2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the Simple View of Reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(1), S25-S44.

- Snowling, M. J., & Hulme, C.(2020). Annual research review: Reading disorders revisited –the critical importance of oral language. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(5), 635-653.

- Wegener, S., Beyersmann, E., Wang, H.-C., & Castles, A. (2022). Oral vocabulary knowledge and learning to read new words: A theoretical review. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 27(2), 253-278.

Please login to view this content

Login