When you say ‘maths’ most people immediately think of numbers… quickly followed by that anxious feeling when their brain makes the connection to times tables. But maths is more than numbers and indeed begins long before numbers with underpinning mathematical language.

‘How many blue triangles?’ seems such a simple question… however to be able to answer it you need to understand what ‘how many’ means, realise that ‘blue’ is a colour and distinguish it from other colours and identify ‘triangle’ as a shape that has three sides and recognise it amongst other shapes. Suddenly the simple question doesn’t seem so simple.

![]()

Maths begins with the development of prenumber skills, which are defined as:

- Making simple comparison

- Identifying same and different

- Matching

- Simple classification

These skills are largely developed through play in the early years and form a part of the Early Years Foundation Stage curriculum delivered at preschool and during the reception year at school. They are assumed to be secure when starting KS1 maths curriculum in year 1. Karen McGuigan, Founder and author of the Maths For Life programme, believes that these prenumber skills should be continued in the curriculum and explored further as a child gains in life experience.

She recognised when she was working with her middle son, Lance, who happens to have Down syndrome, that it was essential to ensure that he had mathematical language to underpin his understanding of numbers. She explains:

“How can we form a ‘5’ with a ‘hat, neck and a big round belly’ if we have no idea what ‘round’ means? How can we draw a ‘7’ as two ‘straight’ lines if no one has ever defined what ‘straight’ means? How can we see that ‘9’ is an upside down ‘6’ if we can’t visualise what ‘upside down’ means?”

By ensuring that mathematical language is modelled daily in everyday life, children can visualise, understand, and apply that language to their learning at school.

“Which one is different?… That one… Why?… Because it’s upside down. Now can you see that a ‘9’ is an upside down ‘6’?”

“Which one is different?… That one… Why?… Because it is the wrong way around.”

“We are too quick to move on from prenumber skills. We tick the box on ‘secured’ when a child can do the obvious ‘the same’ and ‘different’ question. However, it is working through the subtle and classification type questions that really cement the language and connections for the future. It is never about the right answer. It is about being able to articulate the why and having the language to support the rational thought process.”

Karen highlights positional language as another topic that isn’t really seen as maths but again underpins a child’s ability to understand a maths question or indeed a basic instruction.

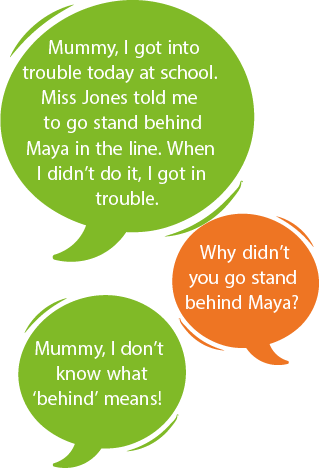

“Mummy, I got into trouble today at school. Miss Jones told me to go stand behind Maya in the line. When I didn’t do it, I got in trouble.”

“Why didn’t you go and stand behind Maya?”

“Mummy, I don’t know what ‘behind’ means.”

Classifying – “It is important to remember that there might be more than one way to classify or answer a question. It is always good to accept the choice given and ask the question why? It leads to more understanding on the thought process of the student.”

“Children are like lemmings – they follow each other.”

Reception teachers rely on the older children in the classroom to understand the instructions and for the younger children to follow them. It is assumed that by following the instructions all the children will develop the understanding of what they mean. This isn’t always the case. It is essential to explicitly teach this positional language and ensure that every child understands.

Positional language is not only used daily in instructions, but it also underpins understanding of maths questions. Think of this question, “How many prime numbers are there in between 10 and 20?” Even if you know what a prime number is, you can’t answer this question correctly if you don’t understand the meaning of ‘in between’.

“When we read an English comprehension or a book, we can get the general gist of the story and context without understanding every single word. We can answer questions and explain what is happening in our own words. In maths it is important to listen and understand all aspects of the question. For example, if we take the question ‘How many boys play football after school on a Wednesday?’ – when we look at the data to select the answer, we must understand that it is only boys, playing football, after school and on a Wednesday that we need to count.”

Positioning – “Getting a student to model positional language using their own body during play or PE is a fantastic way to engage and ensure that concepts are understood.”

Although Karen’s programme ‘Maths For Life’ is a differentiated approach to teaching maths for students with additional learning needs, she believes the principles apply to all children.

“Maths is a series of building blocks and connections. Just like when building a house, you need solid foundations. A key element of this is mathematical language. I believe that if we spend more time ensuring that the language of maths is understood in real life, children will have a more secure platform to make the connections in maths. Parents, teachers, teaching assistants can all make a difference by being more aware of mathematical language and using it daily outside the remit of the maths lesson.”

To find out more about the Maths For Life programme visit the website at www.mathsforlife.com or contact Karen at learn@mathsforlife.com

Please login to view this content

Login