“For too long, we’ve assumed that there is a single template for human nature, which is why we diagnose more deviations as disorders. But the reality is that there are many different kinds of minds. And that is a very good thing.” Jonah Lehrer.

Within education, the term neurodiversity is increasingly being used to promote the view that neurological differences should be recognised and treated in the same way as any other human variation. Neurodiversity refers to the different ways in which our brains function and interpret information. We all naturally think about things in different ways; we have different likes and dislikes, different interests and hobbies, and we are better at some things and poorer at others. Most people are classed as ‘neurotypical’ meaning that their brains function and process information in the way that is expected or seen as ‘typical’ by society.

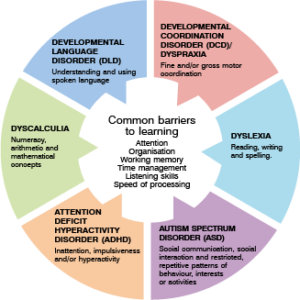

It is estimated that around 1 in 7 people (more than 15% of people in the UK) are ‘neurodivergent’, meaning that their brain learns and processes information differently. The term was originally used by the autistic community, looking to move away from the belief that autism is something medical to be treated or cured, rather than being a valuable part of human diversity. The term Specific Learning Difference (SpLD) is increasingly being used to refer to a number of associated learning differences, including individuals with ASD, ADHD, dyslexia and more recently, DLD.

We have all heard of these diagnostic terms and specific characteristics or ‘differences’ may quickly spring to mind. For children with a diagnosis of ASD, we may instantly think that they will excel at maths and be poor at making friends. But this is definitely not true for all children with this diagnosis. SpLDs are considered to be ‘spectrum’ conditions and although common characteristics occur, individuals vary in terms of the severity and type of difficulties they face. For example, the effects of DLD for one child will be very different to those for another child with DLD. It is really important that children are not stereotyped according to their diagnostic labels.

When supporting children with SpLDs, there can be a tendency to focus on the child’s learning differences and areas of academic weakness. They can be thought of as ‘different’ or ‘strange’ because they learn and process information in a different way to children who are considered to be ‘typical’. They need strategies in place to enable them to access learning. Without this support in place these children are likely to struggle to keep up with their peers, not make academic progress in line with their potential, be more likely to develop mental health difficulties and to leave school or be excluded.

It is recognised that these SpLDs share common barriers to learning and the different conditions will frequently co-occur. This means that it is very beneficial for teaching staff to implement classroom strategies to support these common areas of weakness, as they will support all pupils with SpLDs to better engage with their learning. Here are some examples of strategies for each of these areas:

Attention and Listening Skills

Ensure that you secure a child’s attention, before giving them an instruction or direction. Teach the rules of good listening and use visual prompts as a reminder of these. Encourage children to identify when they don’t understand information and support them to request specific clarification within the classroom, using visual support.

Organisation

Task management boards can support children to understand the steps within a task, so that they know how to start and what the finished task should look like. They can include information about equipment that is needed so that the child can prepare this themselves.

Working Memory

Use short, simple sentences when explaining tasks and break down instructions into smaller chunks. Discuss strategies that can help you to remember spoken information, e.g. visualising things in your head, making lists or writing key points on a white board.

Time Management

Explicitly teach children the meaning of words relating to time, e.g. ‘before’, ‘after’, ‘today’, ‘tomorrow’, using visuals and practical activities, then regularly use these words within context. Use visual timetables, diaries and calendars to support children to orientate themselves in time and develop strategies to improve their time management skills.

Speed of Processing

Support spoken information with visuals, e.g. pictures, symbols, gestures and the written word, so that children do not need to rely only on the spoken word which is fleeting. Use the 10 second rule and allow time for processing before expecting a response.

Once strategies are in place to support these common barriers to learning, it is important to remember that each child is an individual, with their own strengths and weaknesses. It is increasingly being recognised that alongside areas of learning difference, these individuals have areas of strength. For example, individuals with dyslexia are recognised to have strengths in creative, visual and problem-solving skills and as a result are very successful in related careers. The path to achievement can be much harder and require greater effort, due to the impact of the learning difference on areas such as literacy, memory and coordination, but individuals with SpLDs can be very successful.

It is important that teaching staff focus on the child as an individual, regardless of their diagnosis, and identify their profile of strengths and learning differences. This enables strategies to be put in place to support learning differences and the child’s strengths can be celebrated and boosted. It is important to explore methods and techniques to facilitate the optimal learning environment for the child, based on knowledge and experience of the child.

Timetable in activities to celebrate the strengths of all of the children that you are working with, so that we can promote the positive qualities of children with SpLDs. These children are viewing the world in a different way and should be accepted as they are, because their differences are a valuable part of human variation and innovation.

Please login to view this content

Login