In the coming days school staff will be facing possibly the biggest challenge of their careers – ever.

Like almost everyone, they have spent large amounts of time at home, coping with stringent restrictions on daily life, with the ever-present worry of becoming unwell themselves and continual concerns for loved-ones.

Now it’s time to leave the sanctuary of home and prepare to pick up the threads of professional life in a world that has changed. There will be competing priorities and so many questions:

- Who are the most vulnerable children and what are their needs?

- How are we going to meet those needs?

- For some children, will ground gained before the lockdown have been lost?

- How can we even begin to make up for so much lost time?

- How can we keep ourselves and the children safe?

… and all this within the context of social distancing…..

Managing this is the first significant challenge. Children are hard-wired to interact and – particularly for the younger ones – invading others’ personal space is an important part of communication! It might well be a focus of debate – which of these evils will cause the most damage – the risk of Covid 19 or the impact on social, emotional and communication development?

In order to get this right, staff should consider actively teaching effective communication ‘at a distance’. Gone are the opportunities for a child to nudge a friend to gain attention or a member of staff to take a child by the hand to guide him or help explain something.

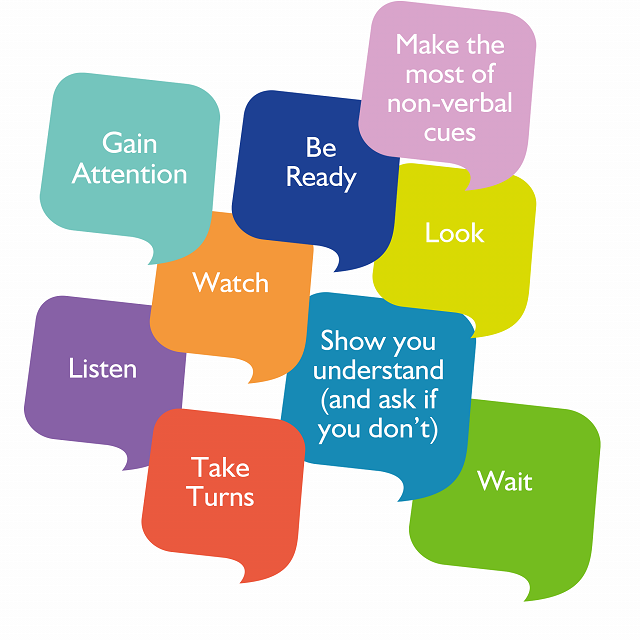

How to be a successful safe communicator. As a minimum, we want children to …

| Be ready | Practice ‘good sitting’. |

| Know how to gain attention | The other person needs to know that you want to start a conversation. Call their name. |

| Be able to take turns | Roles change as we take turns to be the speaker and the listener. |

| Show they can watch, wait, look and listen | This is how we know when it’s our turn. It also helos us to know if what we are saying is reaching the listeners: are they bored? Have they understood? Can they actually hear you? Have you been talking for too long and it’s time for someone else to take a turn? |

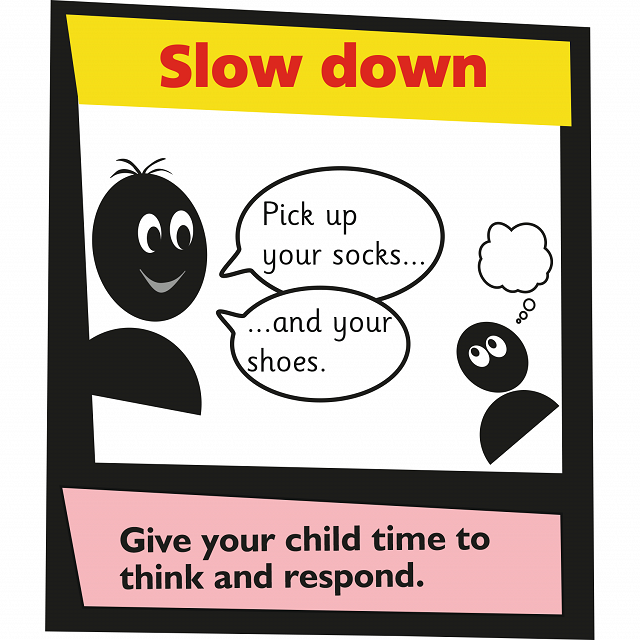

| Speak more slowly | Sound travels fast, but it;s not immediate. |

| Be able to show they have understood (affirmation) | ‘Ok’, nod and smile. |

| Clarify | And ask for an explanation if not. |

| Use and pick up on non-verbal cues | Help get your message across by using gesture and changing. |

In theory, communication ‘rules’ should be embedded in us all…

With the best will in the world however, we know that isn’t always the case! We are used to interrupting, talking over others, using non-verbal means to control the interaction or move things along. We also need to remember that children will be communicating in different types of situations. Here are some typical examples:

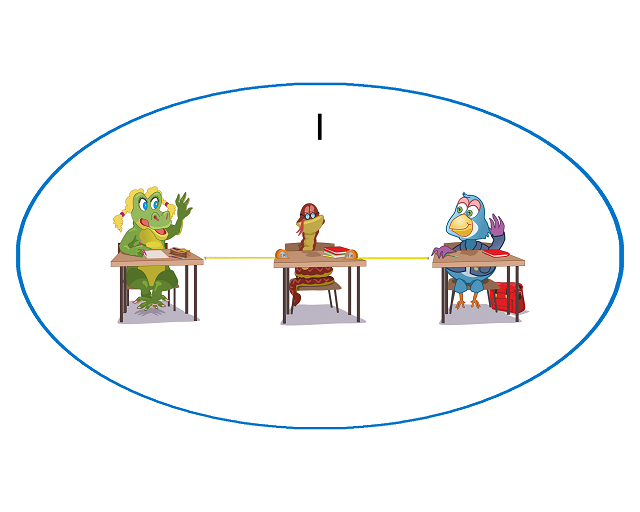

The quite closely-controlled and supervised classroom interactions between adults and children which probably won’t be very far removed from the kind of interaction expected prior to social distancing (putting your hand up, responding to a question etc).

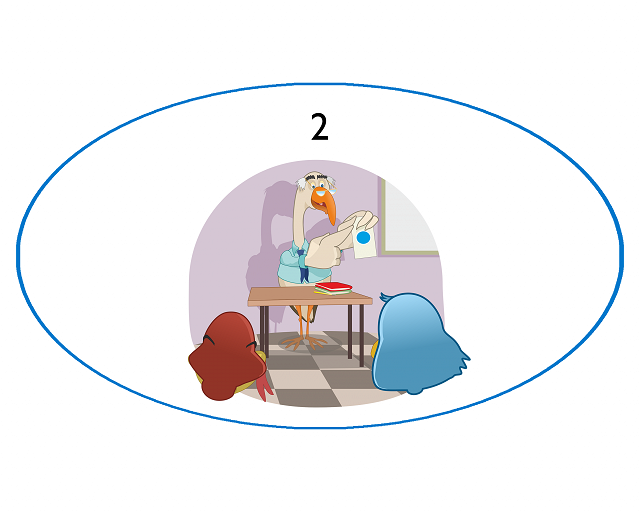

Small group work where children will communicate with each other and an adult: they will talk about their work, ask questions, comment, explain etc. This is the kind of situation where a child might typically and instinctively nudge or touch their neighbour to start an interaction. Now children will need be spaced further apart and it’s time to encourage other ways to get the ball rolling.

Lunch times have a foot in both camps 2 & 4: there will be supervision but it’s likely to be less and children will be spaced further apart. We absolutely want to continue to encourage conversations as this is an important part of social interaction when we sit and eat together. Perhaps the make-up of the small learning groups will be followed through into the dining hall – this would help to maintain the message.

The largely unstructured (and far less closely supervised) interactions which accompany free play. This is probably the biggest risk area: the focus is on fun and movement and it’s easy to forget the new ‘rules’.

Let’s look more closely at those speaker-listener roles. What do children need to know?

| ‘Good sitting’ | Gain attention | Speaker | Listener | Speak slowly |

| Know when to take turns | Show they understand… | … and ask If not | ||

Teaching these things might initially look like a challenging thing to do – and not something you would normally even consider. In the ideal world children learn this by example and if they need reminders, then so be it! But now in the aftermath of Covid 19 we can’t afford to ‘hope for the best’: we need to get it right first time.

Therapists teach ‘speaker-listener rules’. This is usually part of therapy for children for whom this doesn’t come naturally but it can also be part of supporting all children with poor attention and listening skills.

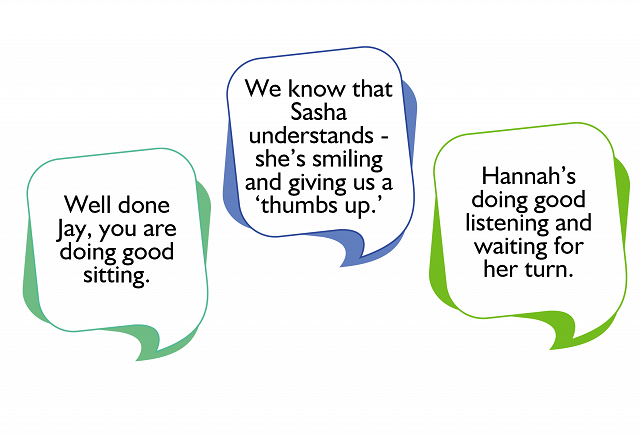

As with any kind of behavioural change, tackled systematically, practised by role play and supported by visual cues and prompts, outcomes are good. You are the best teacher: be a good role model, prompt a child to confirm that s/he understands (or not) and give lots of praise when children get it right.

Poor communicators become better ones, good communicators become even more skilled and, most importantly of all, everyone stays safe.

|

Visual Prompts | ||

| ‘Good Sitting | Being still, watching and waiting. |  |

|

| Gain attention | Put your hand up, say the name of the person you want to speak to. |  |

|

| Speaker | Looking + talking + using non-verbal cues. |  |

|

| Listener | Looking and listening (no talking) |  |

|

| Speak slowly | Remember, sound takes time to travel. |  |

|

| Know when to take turns | It’s hard to talk and listen at the same time |  |

|

| Show they understand | So the speaker knows when to carry on. |  |

|

| And ask if not | Children need to know it’s ok to ask for help. |  |

|