Every child brings an energy and vibrancy to a school classroom – and each can be celebrated for their own unique strengths. But having a child with any kind of impairment or disability can pose additional challenges for a family. For many, their child’s difficulties are part of an emerging story, often coming to the fore as they move through school. While a diagnosis can bring answers, it is often just the beginning of a grieving process for parents.

When we think about grief, it is common to consider those who have lost a loved one and the pain and sorrow following their passing, but grief can present in many different situations when it comes to parenting: A birth plan which wasn’t realised, discovering a child needs glasses, acknowledging an allergy or medical condition, or recognising that a child will need to share time with a partner after a breakup are all valid triggers of a grief process. No grief should be overlooked or undermined. These are crucial stages we move through to come to terms with both loss and change.

Having a child who has a lifelong impairment or disability is a life changing event and brings with it a grief journey like no other.

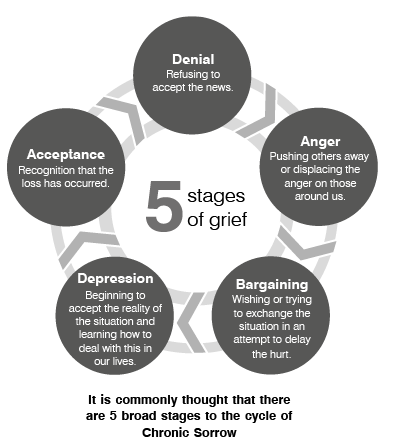

Sociologist Simon O’Shansky suggested in 1962 that this could be described as ‘Chronic Sorrow’; a cyclical grief pattern which never reaches a closing point, but bubbles up at times in life, particularly when direct comparisons can be made, such as transitions and significant life events. Chronic Sorrow is a living loss and one which can affect all family members.

How deeply we feel the pain, how angry we get and how long we stay in each of these stages is completely individual. We may visit this cycle many, many times, triggered by events and memories.

What affects how and when parents grieve?

Support network – Families with close supportive friends and relatives who understand the nature of the child’s difficulties can be of immense support emotionally and practically. Conversely, an extended family member or friend who is not ready to accept the disability of the child, can potentially derail parental awareness, understanding and ultimately acceptance.

Delivery of news – Sensitive and timely delivery of information can make a world of difference to grief. A sensitive and detailed delivery of a diagnosis is paramount at any stage, with parents citing that a brief or unsympathetic sharing of a diagnosis caused greater pain and impacted on acceptance.

Life stressors – Finances, relationships and health all play a part in grief. Parental stress is known to increase when children have a disability.

What does grief look like?

Expect to see a wide range of emotions and feelings around grieving.

Some parents may not accept any potential difficulty or respond with anger to suggestions. This can sometimes be accompanied by a disappointment that the child is not making the progress they had hoped, which is sometimes projected at teaching staff.

Others may appear despairing or lacking in energy or motivation to take anything more on board. These parents are at a crisis point and unable to absorb any further information or advice.

“My barn having burned down, I can now see the moon.” Mizuta Masahide

Some parents will feel a need to do all they can to understand the condition their child has and get help. A busy, informed parent is using these strategies to move through the grief cycle, in their search for meaning and acceptance.

There will also be parents who have embraced and are comfortable to discuss their child’s strengths and needs and are open to suggestions or are able to share their experiences and learning with teaching staff.

What can I do to help?

Sensitivity – With so many factors determining grief, the most important ways to help are by employing tact, sensitivity and giving time. Understanding the stage of grief a family is at will inform the information you give, how you present it and the next steps.

Honesty – It can be difficult to relay information, e.g., on limited progress, regression in skills or difficulties, with a parent who remains in the denial or anger stage. In these situations, it is all too easy to become collusive with families in an attempt to avoid confrontation. Try to maintain communication and ensure that the family receive sensitive but accurate information.

Open door – Sometimes, even with experience, tact and sensitivity it is not possible to maintain a positive relationship with the family. Gauging where a parent is at will inform how we can support them in the most constructive way. Be clear with parents that there is an opportunity to talk further when and if they are ready.

Network – There are some great voluntary agencies and organisations, both locally and nationally which aim to support parents through these difficult times. Be ready to provide this information, if and when they want it.

The relationship that parents have with school staff can provide hope, support and encouragement and to focus on the positive contribution that their child brings to their community.

Please login to view this content

Login