Literacy, while a seemingly innocuous (although incredibly important) topic, stirs up fierce debate across the globe when it comes to which approach we should be using in schools. Here in the UK, the most widely used approach in literacy teaching is ‘Synthetic Phonics’. This approach aims to teach children in a systematic way that speech sounds are associated with particular letters and that letter sounds can be blended together (synthesised) to form a word. Hence the term ‘synthetic’ phonics. The evidence shows us that explicit, systematic teaching of phonemic awareness and phonics benefits a greater number of children in developing literacy skills than ‘business as usual’ teaching (Shapiro and Solity, 2008).

On the other side of this debate however, are proponents of ‘Whole Language’ approaches used in some other countries, such as Australia and New Zealand. Others are somewhere between the two approaches, described by Pamela Snow (Speech Pathologist, Psychologist and Professor at La Trobe University, Australia) as a ‘continuum rather than a dichotomy.’

While it’s far from a simple debate, those supporting both approaches agree on five key elements to literacy success: phonics, phonemic awareness (which falls under the umbrella of phonological awareness), vocabulary, comprehension and reading fluency. Critics of ‘Whole Language’ approaches argue that it does not contain systematic or sequential approach to teaching these elements, and there is a lack of agreed definition of what it involves. Critics of a ‘Synthetic Phonics’ approach argue that a phonics-only approach is not the complete picture.

Learning to read is not a biologically natural process, but rather a (relatively) more recent development over the last few thousand years (Snow, 2016). Supporters of Whole-Language approaches, however, assert that learning to read is as natural a process as developing spoken language. In fact, this is not the case. Spoken language and written language are not acquired in the same way – spoken language requires exposure to language alongside real experience, and written language requires specific teaching and repeated practice (Snow, 2016). Some children do seem to grasp reading incredibly quickly and with little difficulty, however for the average child it requires systematic and repeated instruction. Systematic teaching of phonics means it is achieved with a clear plan – starting on developmentally easier things and working up to the harder stuff.

The two most common reading disorders are to do with comprehension of text (reading comprehension impairment) and decoding (dyslexia) (Snowling and Hulme, 2012). Weak decoding skills signal poor underlying phonological processing abilities, whereas language processing difficulties underpin reading comprehension impairment.

UK research carried out in the 90s compared three different interventions to address weak decoding skills; (1) teacher-reinforced reading strategies with texts at the appropriate level (‘Reading’ intervention), (2) phonological awareness activities, including exercises looking at syllables, rhyme and phonemes – but excluding letter work (‘Phonological Awareness’ intervention) and (3) a ‘Reading + Phonology’ approach, combining the two. This approach taught phonological awareness, letter-sound knowledge and encouraged the children to practise and apply these skills through the reading of texts.

After a 20-week intervention using the three programmes with three different groups, it was clear that the group who participated in the combined programme (Reading + Phonology) were significantly ahead of the other groups, in reading accuracy, spelling and reading comprehension. Gains in the reading element of the programme were maintained five months later. The phonological awareness-only group performed better in phonological awareness tasks unsurprisingly, however this did not generalise to their literacy skills (Hatcher et al, 1994). This research has been used in other studies to develop programmes for classroom teachers, and small group interventions carried out by teaching assistants.

Poor comprehenders (those with reading comprehension impairment) typically have phonological skills in the ‘normal’ range, but often have associated language processing difficulties and poor vocabulary (Nation et al, 2005, Catts et al, 2006). In fact, research has shown that this group of children are likely to have oral language difficulties underlying their reading comprehension impairment, as indicated by poor performance on language comprehension assessments (Cain and Oakhill, 2006). Poor reading comprehenders will demonstrate difficulties with listening comprehension, grammatical understanding, and both receptive and expressive language when they start school – difficulties that then persist throughout childhood. This indicates that poor reading comprehension does not lead to later poor oral language skills, but rather weakness in oral language skills precedes and poses a risk of poor reading comprehension (Nation et al, 2010).

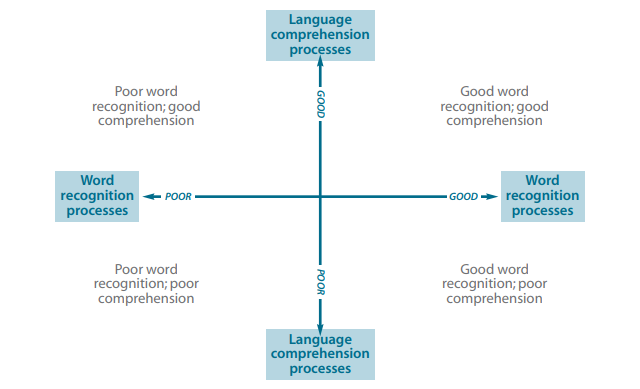

In the Rose Report (2006), the ‘Simple View of Reading’ model was introduced to replace the previous ‘Searchlights’ model. The Simple View of Reading reflects the most up-to-date research into the science of teaching reading, separating out the two crucial components discussed above- word recognition (decoding) and language comprehension. This model made clear the fact that these are two separate processes, and children’s reading strengths and weaknesses can be understood more clearly with reference to this framework.

(Figure from The Rose Report, 2006)

There are four quadrants into which children’s reading profiles can fall- some children will of course have no difficulty whatsoever in learning to read and will sail through with strong word recognition and comprehension skills. Others may have difficulty with word recognition in the absence of comprehension difficulties, and others will have no difficulty decoding but struggle to comprehend what they read. Then there are children who will struggle with both decoding and comprehension. The key to reading instruction, therefore, is to ensure that all children are taught to read effectively, despite their differing profiles.

Earlier we looked at the importance of including systematic phonics instruction as a key part of developing successful literacy skills. Some of you may be thinking ‘phew, we’ve got phonics covered’ – but there is a little more to the phonics instruction that is crucial to its success – and that is a step before letters are ever introduced – teaching ‘phonemic awareness’. This forms one part of the ‘big five’ elements of successful reading (six if you include oral language). Phonemic awareness comes under the larger umbrella of ‘phonological awareness’, which generally speaking is the ability to identify and manipulate the sounds in our language.

Children, on starting school, arrive with varying abilities in the area of phonological awareness. Some children come to school having ‘played’ with speech sounds as a solid part of their ‘play repertoire.’ This may have included singing nursery rhymes, listening to parents/caregivers emphasising sounds in words while reading, noticing and talking about sounds in words or their name, playing ‘I spy’ using phonemes (letter sounds rather than letter names) or talking about sounds or words that sound similar. For others, starting school might be the first time someone has drawn their attention to the sounds in the language they are speaking.

All children, whether they start school with strong or no phonological awareness, will benefit from starting out with phonemic awareness teaching – before letters are introduced in formal instruction. Children must be able to think about the sounds in words before they can link those sounds to letters. This includes learning to segment and blend these sounds to make words. Children with no underlying difficulty will learn the letter-sound relationships anyway, but to give our children who are vulnerable to reading difficulties this solid start, combined with systematic phonics teaching, we are giving them the best chance of developing their early literacy skills.

So now we have emphasised the importance of phonological awareness (particularly phonemic awareness) and the systematic teaching of phonics in the building of our solid foundation for literacy, which leaves us with one of our most vital elements – the development of oral language skills. Oral language skills form a crucial, foundational layer to the building of successful readers. The research tells us that poor reading comprehenders are coming to school with receptive and expressive language difficulties, which persist throughout childhood. It therefore stands to reason that supporting a child’s oral language skills will ultimately positively impact on reading comprehension.

Clarke et al (2010) carried out a large randomised control trial looking at the impact of systematic oral language intervention on reading comprehension in 8-10 year old ‘poor comprehenders’. They used three different programmes of intervention, a text-comprehension training group, an oral language group, and a combined text-comprehension training/oral language group. All groups made greater progress compared to an untreated control group at follow-up. The oral language group, however, made the greatest gains at follow up, and along with the combined text-comprehension and oral language group, demonstrated significant gains in expressive vocabulary compared with the control group.

Better language skills will lead to stronger listening abilities (children who have language comprehension difficulties can often ‘switch off’ in the classroom which can be perceived as attention and behavioural difficulties). This means children receiving oral language support will better access the teaching in the classroom, including reading instruction. Stronger language skills also extend to increased vocabulary comprehension and understanding of syntax (sentence structure) and grammar, all of which support reading comprehension.

Let’s take the big five elements of successful reading (phonics, phonemic awareness (as part of phonological awareness), vocabulary, comprehension and reading fluency), and add ‘oral language skills’ to the mix. All children should have access to a language-rich environment in the classroom, a strong foundation in phonological awareness (and phonemic awareness), and systematic phonics instruction. This ensures that most children will receive the right recipe for building solid literacy skills. For those who need an extra level of support, small group interventions should be implemented, and for those who struggle the most, personalised, targeted 1:1 interventions. Sir Jim Rose (2009) writes about these levels of intervention as ‘waves’ in his independent report to the Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, titled: ‘Identifying and Teaching Children and Young People with Dyslexia and Literacy Difficulties.’

As we all know, children don’t fit neatly into boxes, clearly labelled with a ‘pure’ diagnosis. Rather, they come to us with a multi-faceted profile of strengths and needs that often overlaps with different diagnoses. It is not practical or advisable to isolate all children into groups according to their phonological or language processing abilities and devise different pathways to teaching reading in the classroom. A far more effective strategy would be to take what we know from the research and cover all of the main strands of effective reading instruction for the whole class. Most children will benefit from this combined approach, and this is far more practical to implement. Children who then fall behind their peers can be identified and given a further level of support. Phonological skills + oral language skills = a solid foundation for literacy development.

We have evidence from academics who are also education professionals, reading experts, speech and language therapists, psychologists and more. What’s clear is that we all need to work together to create the blueprints for building successful reading instruction for all children.

Try some of these activities to support phonological awareness in the Early Years Foundation Stage:

Support environmental listening, by encouraging the children to tune in to environmental sounds:

Listening walks – encourage the children to quietly listen to the sounds around them. Talk about the sounds they can hear.

Making music with the things around us – explore the different sounds you can make by tapping or knocking different objects in the playground.

Guess the musical instrument – sit the children in a circle and offer them a feely bag from which to choose an instrument. The adult has one of every instrument too. The adult then selects an instrument and plays the sound without letting the children see. The child who has the matching instrument must stand up.

Try these phonological awareness activities:

Share rhyming books with the children, encouraging them to join in with the repetitive phrases, e.g. ‘I would not like them here or there, I would not like them anywhere….’

Sing nursery rhymes and rhyming songs regularly, emphasising the rhyming words and encouraging all the children to join in. Try leaving out a rhyming word and have the children fill in the gap.

‘Guess what I’m clapping’ – select a few familiar objects and place them in the middle of a circle where the children are sitting. Talk about the names of the objects and clap out the syllables as you go. Now clap out the syllables without naming an object and see if the children can guess which word you are clapping.

Try these phonemic awareness activities:

I spy names – The adult says ‘I spy someone whose name begins with….ssssss.’ Any children whose name begins with that sound should stand up. Once the children know how it works, they can take turns being the person who spies.

Use a feely bag, or objects buried in sand to create a small collection of items beginning with the same sound. You could have two groups, distinguishing between two different sounds, e.g. ‘bus’, ‘ball’, ‘bell’ in one group, and ‘car’, ‘cow’ and ‘cup’ in another.

Mirror play – use some small mirrors or take turns with one large mirror for the group. Choose a sound and encourage children to watch the movements of their lips and tongue as they copy it.

Oral blending – during story time, choose some simple, keywords from the story to segment and then blend together, e.g. ‘I like green eggs and h – a – m – ham!’

Toy Talk – Use a soft toy, e.g. a teddy, who only speaks in ‘Toy Talk’ (segmented words) to ‘whisper’ in your ear. Ask it questions, such as ‘What’s your favourite food?’ Teddy should ‘whisper’ in your ear, which you can then repeat back to the children- ‘ch – ee – se’? Oh, cheese!’ Invite the children to speak in ‘Toy Talk’ just like teddy.

These activities have been taken from Phase One of the ‘Letters and Sounds’ programme, from the Primary National Strategy 2007. This programme contains an extensive list of phonological and phonemic awareness activities to support the early stages of a phonics programme.